Dr. Dinesh Thavendiranathan is a leading expert in cardio-oncology.

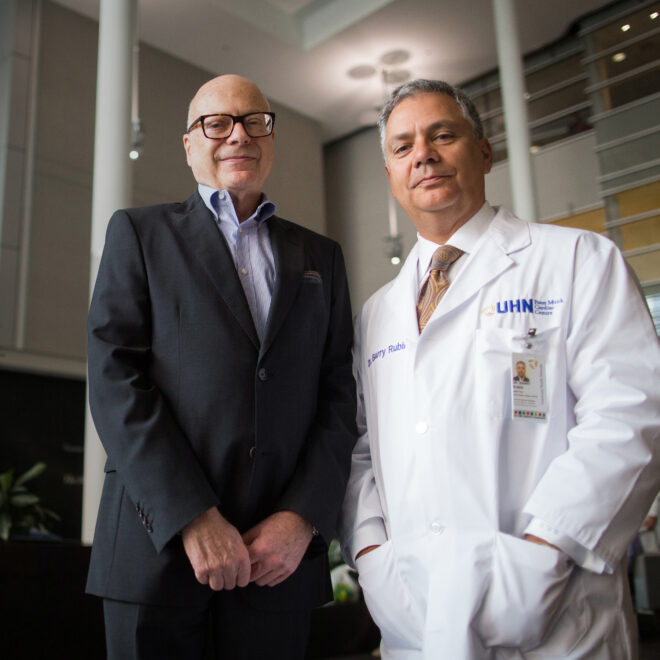

Tim Fraser

A better and brighter tomorrow

Thanks to the groundbreaking research and extraordinary care at the Ted Rogers Centre for Heart Research and the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre, people suffering from heart damage caused by the unintended consequences of cancer treatments have a brighter future.

When a patient undergoes chemotherapy or radiation to address cancer, the last thing on their mind is heart disease. Although cancer therapies are becoming more effective in destroying cancer cells, these therapies can be toxic to the heart and result in adverse side effects known as cardiotoxicity, including abnormal heart rhythm – arrhythmia, thickening of heart muscle called cardiomyopathy, and in severe cases, heart failure.

“I felt really cared for and a part of my care.”

Maya Stern

What makes treating these adverse side effects challenging is that each patient may present different symptoms. Collaboration among cardiologists, oncologists, researchers and patients – like that at University Health Network’s Peter Munk Cardiac Centre Cardiotoxicity Clinic and the Ted Rogers Cardiotoxicity Prevention Research Program – is crucial to better understanding how cardiotoxicity develops in patients and how to treat and prevent it.

A new standard of care

The Ted Rogers Cardiotoxicity Prevention Research Program at the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre was established in 2013 to research patients at risk of, or experiencing heart complications from cancer therapy. Now, the program has expanded its research to investigate how this heart damage develops and determine optimal cancer therapies for each patient. Patients with cardiotoxicity and who may be at risk are seen and treated separately at the clinical program at the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre – the largest cardiotoxicity clinical program in Canada, providing care for more than 2,000 patients each year.

“The team continues to follow [patients] closely to prolong the health and strength of the heart.”

Dr. Dinesh Thavendiranathan

The research program, led by cardiologist Dr. Dinesh Thavendiranathan, who also leads the clinical program, is driven by groundbreaking research, offering advanced cardiac monitoring strategies and a series of therapies aimed at preventing and treating cardiotoxicity. Oncologists and cardiologists work collaboratively to prevent heart problems during and after cancer treatments, and patients are educated and empowered to self-manage their symptoms, including sleep and stress management, exercise and diet.

“Long after the oncologist has stopped seeing patients who are cancer free, the cardiotoxicity program team continues to follow them closely to prolong the health and strength of the heart,” explains Dr. Thavendiranathan.

He reveals, “Our research shows that in women with certain subtypes of breast cancer, for example, there is up to 10 per cent risk of heart failure. That’s a three- to five-fold increase versus the risk of heart failure in the average person.” Since a link has been established between heart failure and common breast cancer therapies, the team has identified a new standard of care recommending collaboration between oncology and cardiology teams, cardiovascular risk assessment and early detection. “In our program, with advanced cardiac monitoring and early intervention strategies, the risk of heart failure has been reduced to zero per cent.”

Now, the Ted Rogers Cardiotoxicity Prevention Research Program team aims to expand global knowledge on the unique challenges in cardio-oncology and continues to foster new avenues of research to understand the risk of cancer treatments to the heart.

10%

Research at the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre shows there is up to 10 per cent risk of heart failure in women with certain subtypes of breast cancer, for example – a three- to five-fold increase versus the risk of heart failure in the average person.

The heart that could

In 2004, before the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre established its cardiotoxicity program, Maya Stern was diagnosed with heart disease after overcoming childhood cancer. Her health became a constant interruption to leading a normal life. Before she graduated high school, Stern experienced a clot in her ulnar artery and a stroke.

As a teenager, Stern was referred to Dr. Heather Ross, Head of the Division of Cardiology at the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre and Scientific Lead for the Ted Rogers Centre for Heart Research. To control her heart’s abnormal rhythm and stabilize her worsening heart condition, Stern received a pacemaker.

“In our program, the risk of heart failure has been reduced to zero per cent.”

Dr. Dinesh Thavendiranathan

By the time Stern was 21 years old, she was forced to stop her education at York University and had experienced just how bad cardiac disease can get. After suffering cardiac arrest during a medical intervention, Dr. Ross, who also holds the Loretta A. Rogers Heart Function Chair and Pfizer Chair in Cardiovascular Research, placed her on the heart transplant list. After just 10 days, she received a new heart. Although Stern’s condition was dire, the team was equipped to handle all of her needs, and she considers her referral to the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre a game changer for her heart health.

30%

Breast cancer patients with one or two risk factors who experience a cardiac event.The Scientist

Dr. Husam Abdel-Qadir happened to be the resident cardiologist on call when Stern went in for her transplant. Stern recalls, “On the night before my transplant and for two weeks after, Dr. Abdel-Qadir took such a personal interest in my health, and I appreciated his heartfelt and dedicated care.”

Inspired by Stern’s story, Dr. Abdel-Qadir decided to pursue a career in focussing on patients with cardiotoxicity. Dr. Abdel-Qadir is now a staff cardiologist and a clinician scientist at Women’s College Hospital and the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre and is an integral part of the Ted Rogers Centre for Heart Research Cardiotoxicity Prevention Research Program.

Life after treatment

In January 2021, when Stern was asked by Dr. Abdel-Qadir to become a patient partner with the Ted Rogers Cardiotoxicity Prevention Research Program, she was enthusiastic. “This was a chance for me to take what was not a great experience for me and have some good come out of it.”

Patients like Stern can help the research team by providing a patient context to interpret study results and helping develop research questions. This collaboration is helping to drive future research so the team can continue studying the effects of cardiotoxicity on the heart which will ultimately lead to better patient outcomes.

As Stern explains, “This research has an immediate application to people who are suffering from the unintended consequences of cancer therapy. It can be translated and applied in the short term. It’s actionable. I love that I can play a role in helping others.”

“I have a plan, and now, I have the capacity.”

Maya Stern

Today, Stern has enjoyed almost 12 years with a healthy heart and continues to be cancer free. Her future looks bright as Stern is completing her second master’s degree at the University of Toronto and is working toward a career in social work. “I have a plan, and now, I have the capacity.”

Remarkable in its collaborative and preventative focus, the Ted Rogers Cardiotoxicity Prevention Research Program at the Peter Munk Cardiac Centre is also the first of its kind. “No one across the world has been able to have a program like this one,” says Dr. Thavendiranathan. “The team here is so collaborative, so human, so intelligent and yet so kind. I feel supported. I hold this close to my heart.”